http://hyperallergic.com/315313/a-deep-dive-into-the-legacy-of-las-surrealists/?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=A%20Deep%20Dive%20into%20the%20Legacy%20of%20LAs%20Surrealists&utm_content=A%20Deep%20Dive%20into%20the%20Legacy%20of%20LAs%20Surrealists+CID_22572fdffbb4eb824b16ae8d5b158502&utm_source=HyperallergicNewsletter&utm_term=A%20Deep%20Dive%20into%20the%20Legacy%20of%20LAs%20Surrealists

A Deep Dive into the Legacy of LA’s Surrealists

Cameron, “Sebastian (Imaginary Portrait of Kenneth Anger)” (1962), ink and gouache on paper, 20 x 30 inches (all images courtesy the artist and Richard Telles Fine Art)

LOS ANGELES — The official Made in L.A. show is at the Hammer Museum, but a felicitous counterpoint is currently at Richard Telles in the Fairfax district. Made in L.A., the third in a biannual exhibition at the museum, features artists who are already highly regarded, or else anointed as up-and-coming, whereas Telles presents a historical group show of 20th-century LA surrealists who, in many cases, were never much known outside their own circle. Curated by Max Maslansky (himself a Made in L.A. alumnus from 2014), Tinseltown in the Rain is a deep dive into an important aspect of this city’s art history that has much to offer to our present moment.

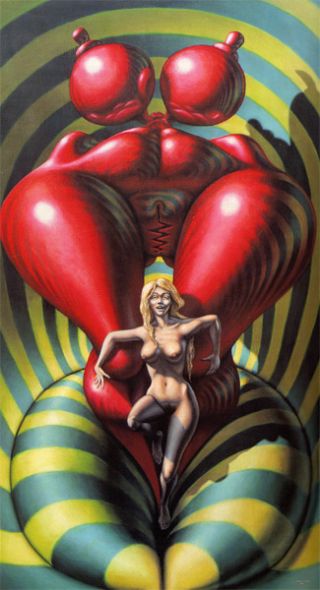

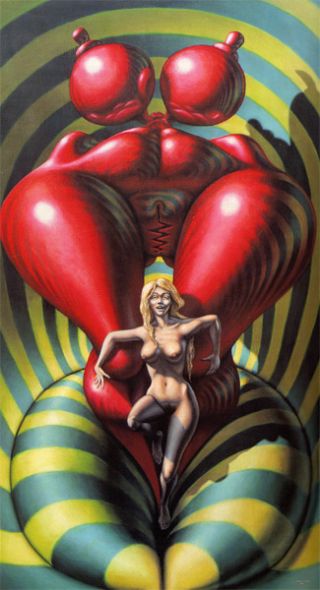

Robert Williams, “Ernestine and the Venus of Polyethylene” (1968), oil on canvas with ground fish-scale highlights, 50.25 x 29.5 inches (click to enlarge)

Made in L.A. includes a lot of artists addressing Los Angeles and its film industry in particular, most obviously Daniel Small’s excavation of Cecil B. DeMille’s destroyed set for The Ten Commandments. Telles’s small, focused show demonstrates how Surrealism permeated Hollywood, presenting a selection of videos including Loony Tunes and Disney animations, as well as films including “Meshes of the Afternoon” by Maya Deren and her husband at the time, Alexander Hammid. Oskar Fischinger’s synesthetic/psychedelic “Optical Poem” (1937) is a stop-motion animation of colorful geometric shapes set to Franz Liszt’s Second Hungarian Rhapsody. It feels a lot like early special effects on MTV and has a strong kinship with Kandinsky’s fusion of music and visual art. Maslansky’s well-researched exhibition essay recounts how Walt Disney hired European émigrés, including artists in this show, who inflected the company’s visuals with the surreal imagery they brought with them from the continent.

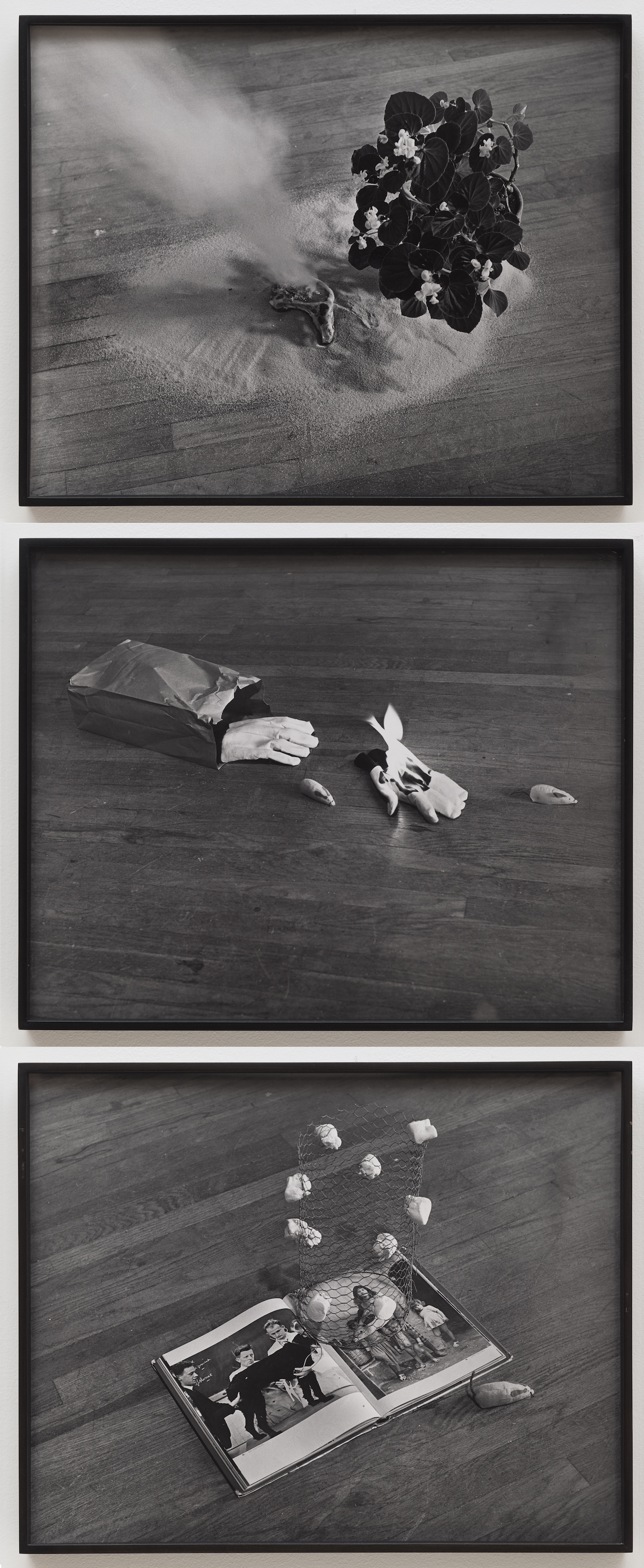

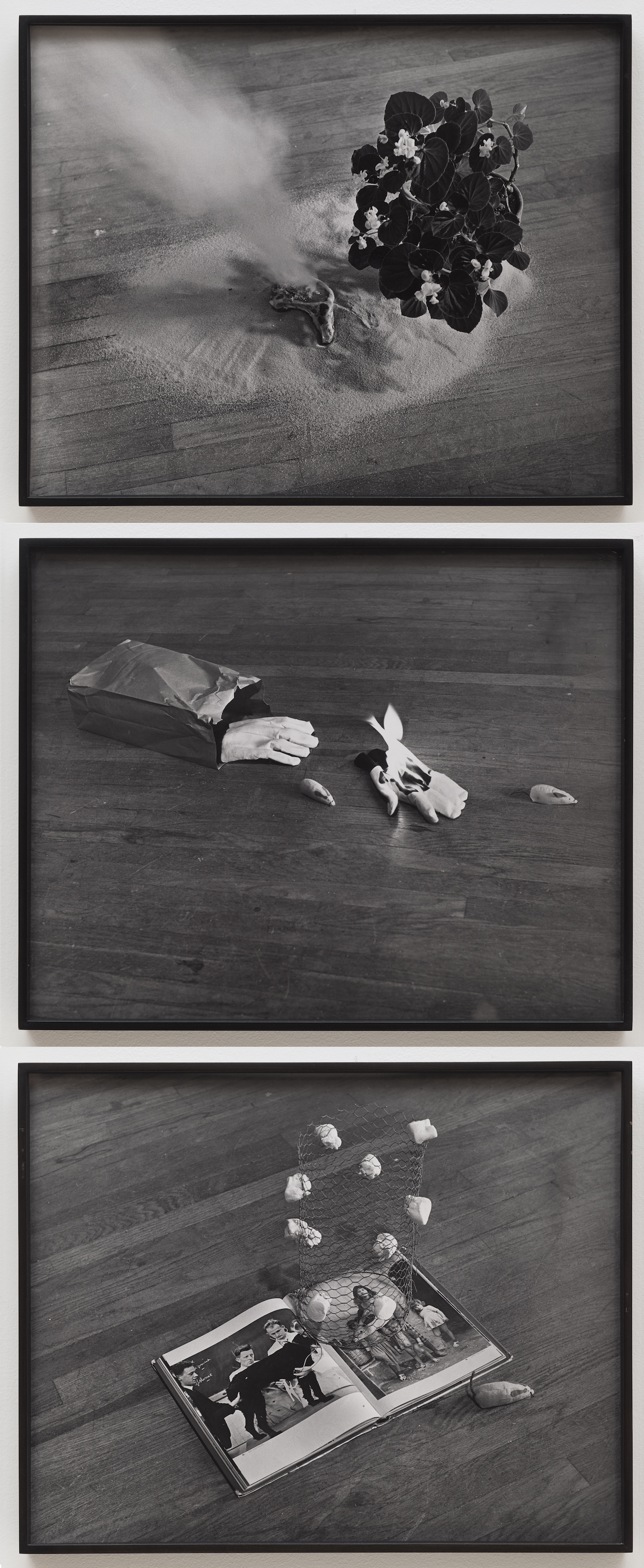

Sharing the video room are mostly photographs, of which I was particularly taken with William Leavitt’s “Random Selection: Bag, Glove, Fire, Mice” (1969), consisting of three photographs of unrelated items arranged to imply peculiar narratives — the middle picture shows two stuffed mice seemingly escaping from a paper bag along with two gloves that have come to life, one of them bursting oddly into flames. Edmund Teske’s two images titled “George Herms, Topanga Canyon” (1962) find Herms standing naked in the chaparral like a dazed amnesiac. The single painting in this room is a knockout by Robert Williams (who also made art for Zap Comix), “Ernestine and the Venus of Polyethylene” (1968) depicting a nude woman standing below a towering red female statue, seen from below and balloon-like in form, appearing to be made of highly reflective stainless steel. In this bizarre image Williams anticipates both Jeff Koons and John Currin (Currin seems to have learned the figure from Williams as much as from the van Eyck brothers). The impressively shiny highlights on the balloon-woman are made with ground fish scales, a material I would not have expected to survive for half a century.

Installation view of ‘Tinseltown in the Rain: The Surrealist Diaspora in Los Angeles 1935–1969’ at Richard Telles, Los Angeles

All the other paintings and drawings are hung in the main gallery, on a single wall beginning at eye level and ascending toward the ceiling, salon-style. I felt as though I had walked into Gertrude Stein’s Parisian home, which was fun, though I had a crick in my neck by the time I left the gallery (we must suffer for art). On this wall the influence of Picasso looms large, with a few other canvases taking after Dalí or Klee. The work in this room clarifies that these LA artists, though many hailed from Europe, were not your mother’s (or grandmother’s) Surrealists. You will not find dream-like scenes à la Max Ernst, for example, but will instead see less familiar strains of Surrealism that grew out of the original experiments in the Continent.

William Leavitt, “Random Selection: Bag, Glove, Fire, Mice” (1969), unique black and white photos (3 parts), 15.5 x 19.5 inches each (click to enlarge)

Cameron’s work stuck in my mind with its witchy mystery. Her ink drawing “Sebastian (Imaginary Portrait of Kenneth Anger)” (1962) portrays Anger, her husband, as both female and male, melting into the earth while a house sits either atop or behind him. Her untitled drawing of a demon is alive with elusive energies. Cameron at times burned her work sacrificially, “not as a symbolic gesture,” Maslansky writes, “but as a means to reach deities.” Noah Purifoy has a smashed metal canteen in a wooden frame, simple and forceful, with the well-chosen title “Pressure” (1966). An assemblage piece by Ed Kienholz, “My Mother Was an Antique Table” (c. 1956), is a tall rectangular panel pierced by a semicircle of dowels toward the top, which are encircled by looping skeins of paint that trickle down. The work retains power despite the abundance of such work ever since Rauschenberg, a signal that Kienholz had a tremendous visual instinct. Beatrice Wood’s ceramic bas-relief “Three Buttocks” (ca. 1960s) is exactly what its title suggests, and feels uniquely fitting to our present moment in American presidential politics in which our Republican presidential candidate’s statements sound mostly like flatulence. I am reminded of the Mike Judge 2006 satire “Idiocracy,” which imagines the latest hit movie to be a two-hour close-up of somebody’s ass periodically farting.

Why look at Surrealism now? Far from being a throwback exhibition, the concerns of this period speak with sharp urgency. Fifteen of the exhibited works were made just before or during World War II, the remainder as the US was ramping up to the social upheaval of the 1960’s and ‘70s. Our 21st century has much in common with both these periods. Fascism and hate-based politics are gaining global ground in a manner reminiscent of the late 1930s, and the American social fabric seems to be wearing as disenfranchised populations demand overdue justice. It’s not that any works in this exhibition address these issues, but rather that the deep premise of Surrealism offers a cogent response to political coercion, technocratic authority, and violence. The surreal, with its irrational heartbeat, slips beyond the grasp of enforcement, creating a small space for alternative cultures to whisper their secrets.

Tinseltown in the Rain: The Surrealist Diaspora in Los Angeles 1935–1969 continues at Richard Telles through August 13.

.jpg?mode=max?w=780)

No comments:

Post a Comment